Open banking works by allowing third-party financial service providers to access your bank account data through secure application programming interfaces (APIs), but only after you explicitly grant permission. When you connect a budgeting app to your checking account, for instance, you’re authorizing your bank to share specific transaction data with that app””your bank sends the information through a standardized API connection rather than requiring you to hand over your login credentials. This shift from screen scraping (where apps logged in as you) to API-based access represents a fundamental change in how financial data moves between institutions. The practical result is that a startup building a lending product can instantly verify an applicant’s income by reading bank statements directly, rather than asking for PDF uploads or manual verification.

A small business owner can see all their accounts from different banks in one dashboard. An accounting platform can automatically categorize transactions without the business owner logging into multiple portals. The technology itself isn’t revolutionary””APIs have existed for decades””but the regulatory frameworks and banking industry cooperation that make open banking possible are relatively new, having gained serious momentum only since 2018. This article covers the technical infrastructure that enables open banking, the regulatory landscape driving adoption, security mechanisms protecting your data, how startups are building on these rails, and the limitations founders should understand before integrating open banking into their products.

Table of Contents

- What Technical Infrastructure Makes Open Banking Work?

- The Regulatory Frameworks Driving Open Banking Adoption

- Security Mechanisms and Consumer Consent Architecture

- How Startups Are Building Products on Open Banking Rails

- Limitations and Failure Points Founders Should Understand

- The Economics of Open Banking for Third Parties

- Where Open Banking Is Heading

- Conclusion

What Technical Infrastructure Makes Open Banking Work?

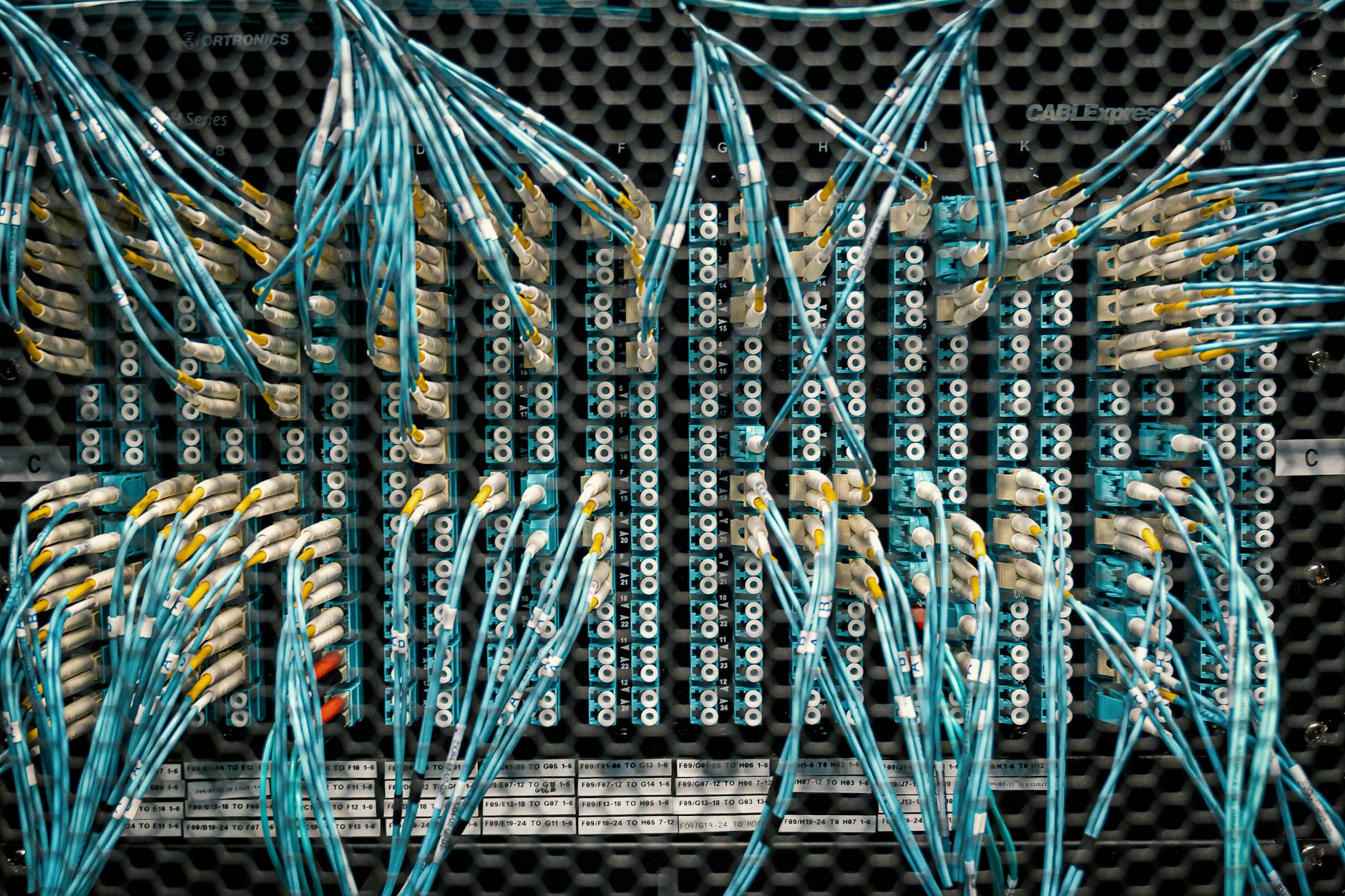

open banking relies on a layered technical architecture that connects banks, third-party providers, and consumers through standardized protocols. At the foundation sits the API layer””banks expose specific endpoints that allow authorized applications to request account information, initiate payments, or verify identity. These aren’t generic APIs; they follow specifications like the UK’s Open Banking Standard, the Berlin Group’s NextGenPSD2 framework in Europe, or the Financial Data Exchange (FDX) standard gaining traction in the United States. The connection process typically works like this: when a user wants to link their bank account to a fintech app, the app redirects them to their bank’s authentication portal. The user logs in directly with their bank, approves specific permissions (read transaction history, view balances, initiate payments), and the bank issues an access token to the third-party app.

This token has limited scope and expiration””the app can only access what the user approved, and access can be revoked at any time. The OAuth 2.0 protocol underpins most of these authorization flows, providing a standardized way to grant limited access without sharing passwords. In practice, most startups don’t connect directly to bank APIs. Instead, they use aggregation platforms like Plaid, Yodlee, TrueLayer, or Tink that maintain connections to thousands of financial institutions. These aggregators handle the complexity of different API implementations, authentication flows, and data normalization. A startup integrating Plaid’s API, for example, gets a consistent data format regardless of whether the end user banks with Chase, a regional credit union, or an international bank.

- —

The Regulatory Frameworks Driving Open Banking Adoption

Regulation has been the primary catalyst for open banking, though the approach varies dramatically by region. The European Union’s Revised Payment Services Directive (PSD2), which took effect in 2018, mandated that banks provide API access to licensed third parties. This wasn’t optional””banks that refused faced regulatory penalties. The UK went further with its Open Banking Implementation Entity, which not only required the nine largest banks to open their APIs but also specified exactly how those APIs should work, creating genuine interoperability. The United States has taken a market-driven approach rather than a regulatory mandate, which explains why open banking infrastructure is more fragmented there.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau issued a rule in late 2023 under Section 1033 of the Dodd-Frank Act that will eventually require banks to share data through APIs, but full implementation won’t happen until 2026 for large banks and even later for smaller institutions. Until then, much of what passes for “open banking” in the US actually relies on screen scraping or bilateral agreements between banks and aggregators. However, if you’re building a fintech product, regulatory status matters enormously for your liability and business model. In the EU, you need to be licensed as an Account Information Service Provider (AISP) or Payment Initiation Service Provider (PISP) to access bank APIs directly””or you need to work through a licensed entity. In the US, the regulatory picture is murkier, and banks can (and do) cut off access to aggregators they consider problematic. The 2022 dispute between Plaid and PNC Bank, where PNC blocked Plaid’s access and forced customers to re-link accounts, illustrates how fragile these connections can be in an under-regulated market.

- —

Security Mechanisms and Consumer Consent Architecture

Open banking’s security model addresses the fundamental problem of the pre-API era: credential sharing. Before standardized APIs, connecting a financial app to your bank typically meant giving that app your username and password. The app would then log in as you, scrape the screen for data, and store your credentials. If the app got breached, attackers had direct access to your bank login. The current model eliminates credential sharing through tokenized access. When you authorize a fintech app, you authenticate directly with your bank””the third party never sees your password. The bank issues an access token that grants specific, limited permissions.

These tokens typically expire after 90 days in regulated markets (requiring you to re-authorize), and you can revoke them at any time through your bank’s portal. Strong Customer Authentication (SCA), required under PSD2, adds additional layers””typically two-factor authentication involving something you know (password), something you have (phone), or something you are (biometric). Banks also implement rate limiting, encryption requirements, and audit logging for API access. Every data request from a third party gets logged, creating an accountability trail. That said, security isn’t absolute. The consent process itself can be confusing for consumers””research from the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority found that many users don’t fully understand what permissions they’re granting. And while the API layer might be secure, the third-party apps themselves vary widely in their security practices. A poorly secured fintech startup with access tokens to thousands of bank accounts presents a real aggregation risk.

- —

How Startups Are Building Products on Open Banking Rails

Open banking has enabled entirely new business models while fundamentally changing how existing financial services work. The most visible category is personal finance management””apps like Emma, Cleo, or Copilot that aggregate all your accounts, categorize spending, and provide budgeting insights. These products literally couldn’t exist at scale without API-based access to transaction data. The same infrastructure powers the “round-up and invest” feature in apps like Acorns, which monitors your transactions in real time to sweep spare change into investment accounts. Lending and credit represent another major application. Traditional underwriting relies heavily on credit scores, which disadvantage thin-file borrowers””immigrants, young adults, or anyone who hasn’t used much credit.

Open banking allows lenders to underwrite based on actual cash flow: analyzing months of bank transactions to verify income, assess spending stability, and predict repayment likelihood. Companies like Petal in credit cards or Kabbage (now part of American Express) in small business lending pioneered this approach. For the borrower, it often means faster approval with less documentation; for the lender, it can mean better default prediction than traditional credit scores provide. Accounting and invoicing platforms have integrated open banking to eliminate manual bank reconciliation””when transactions flow directly into QuickBooks or Xero via API, the small business owner stops typing in numbers from bank statements. Payment initiation, allowed under PSD2, lets e-commerce sites offer “pay by bank” options that bypass card networks entirely, reducing fees for merchants. The trade-off for startups building on these rails: you’re dependent on infrastructure you don’t control, and aggregator pricing can change. Plaid’s pricing, for example, isn’t public and varies by use case and volume””a cost structure that’s hard to model when you’re pre-revenue.

- —

Limitations and Failure Points Founders Should Understand

Open banking coverage is neither universal nor consistent. In the UK and EU, the major banks must provide APIs, but the data available through those APIs can be limited. Many open banking implementations only expose transaction data for the past 90 days, which isn’t enough for serious underwriting analysis. Business accounts often have worse API support than consumer accounts. Some banks implement APIs that technically meet regulatory requirements but provide poor user experiences””slow response times, frequent authentication timeouts, or confusing consent screens that cause users to abandon the linking process. In the US, the coverage problem is more severe. While aggregators claim connections to thousands of institutions, the quality varies enormously. Major banks generally work well, but regional banks and credit unions often have degraded experiences.

Screen scraping still fills gaps where APIs don’t exist, and screen scraping breaks whenever the bank updates their website. Plaid’s status page regularly shows partial outages at various institutions. If your product’s core value proposition depends on reliable bank connections, you need to account for 5-15% of users who will have persistent linking problems. Performance also degrades in ways that matter for product design. Real-time balance checks aren’t truly real-time””they might reflect data from hours ago. Transaction categorization from aggregators isn’t always accurate. International banks outside the UK/EU often have no open banking support at all. If you’re building a product that needs to know someone’s exact available balance before initiating a payment, open banking alone won’t give you that confidence. You’ll need fallback mechanisms, user-reported data, or partnerships that go beyond standard aggregator connections.

- —

The Economics of Open Banking for Third Parties

Using open banking infrastructure isn’t free, and the pricing models affect product economics significantly. Aggregators like Plaid, MX, or Yodlee typically charge per connection per month, with pricing that can range from a few cents to several dollars depending on the data accessed, the volume, and the use case. Identity verification and instant account verification commands premium pricing. A fintech app with 100,000 active users each linking one bank account might pay $20,000 to $50,000 monthly just for data access””before building anything else.

For comparison, Stripe’s Plaid integration pricing (which Stripe publishes) runs $0.30 per bank account verification for the basic tier. That sounds cheap until you realize that a savings app might need to verify accounts multiple times as users add and re-link institutions. Direct bank API access, where available, can be cheaper””but maintaining those integrations yourself requires significant engineering resources. The build-versus-buy calculus shifts depending on your scale: a startup processing 1,000 connections per month almost certainly should use an aggregator; a company processing millions might justify the engineering investment to reduce per-transaction costs.

- —

Where Open Banking Is Heading

The trajectory points toward broader data access and deeper integration into financial infrastructure. The EU’s proposed Financial Data Access (FIDA) framework would extend open banking principles beyond payment accounts to insurance, investments, and pensions””creating what some call “open finance.” The UK is similarly consulting on expanding beyond the original nine banks to include more institutions and more data types. In the US, the CFPB’s 1033 rule implementation will eventually bring regulatory backing to what’s currently a patchwork market.

Variable Recurring Payments (VRPs), already launched in the UK, represent the next functional expansion””allowing third parties to initiate recurring payments from bank accounts without going through card networks, potentially disrupting how subscriptions and utility payments work. For founders, the strategic implication is that open banking infrastructure will become increasingly foundational. Products built on these rails today will have advantages as the ecosystem matures; products that ignore open banking may find themselves at a disadvantage as consumers expect seamless financial data connectivity.

- —

Conclusion

Open banking transforms how financial data moves by replacing credential sharing with token-based API access, governed by user consent and (in regulated markets) specific technical standards. The practical result is that third-party applications can read account information and, in some jurisdictions, initiate payments””without ever seeing your bank password. This infrastructure enables product categories from budgeting apps to alternative lending to automated accounting, though with meaningful limitations around coverage, reliability, and cost.

For founders building in adjacent spaces, the key considerations are regulatory jurisdiction (which determines what’s legally accessible and how), aggregator selection (which affects reliability and cost structure), and product design that accounts for imperfect data. Open banking isn’t a magic solution for financial data access””it’s a significant improvement over what came before, with its own constraints and failure modes. Understanding those constraints before building on the infrastructure will save considerable frustration.